This is part 4 of a series of posts:

In episode 3 we worked through an implementation of AirDrop using C# that allows receiving files between Apple devices. In this episode we’ll look at implementing the bits necessary to open this up to non-Apple devices.

The Plan

Now that we can send files between Apple devices we’re in a good position to start opening things up to non-Apple devices. However, as mentioned in episode 1, it is unlikely that a non-Apple device has hardware support for adhoc wireless connections between devices. This makes implementation of AirDrop directly on non-Apple devices practically impossible without additional hardware. Instead we’ll implement a proxy that can run on a platform with supported hardware (e.g. an Apple device or Linux device running OWL).

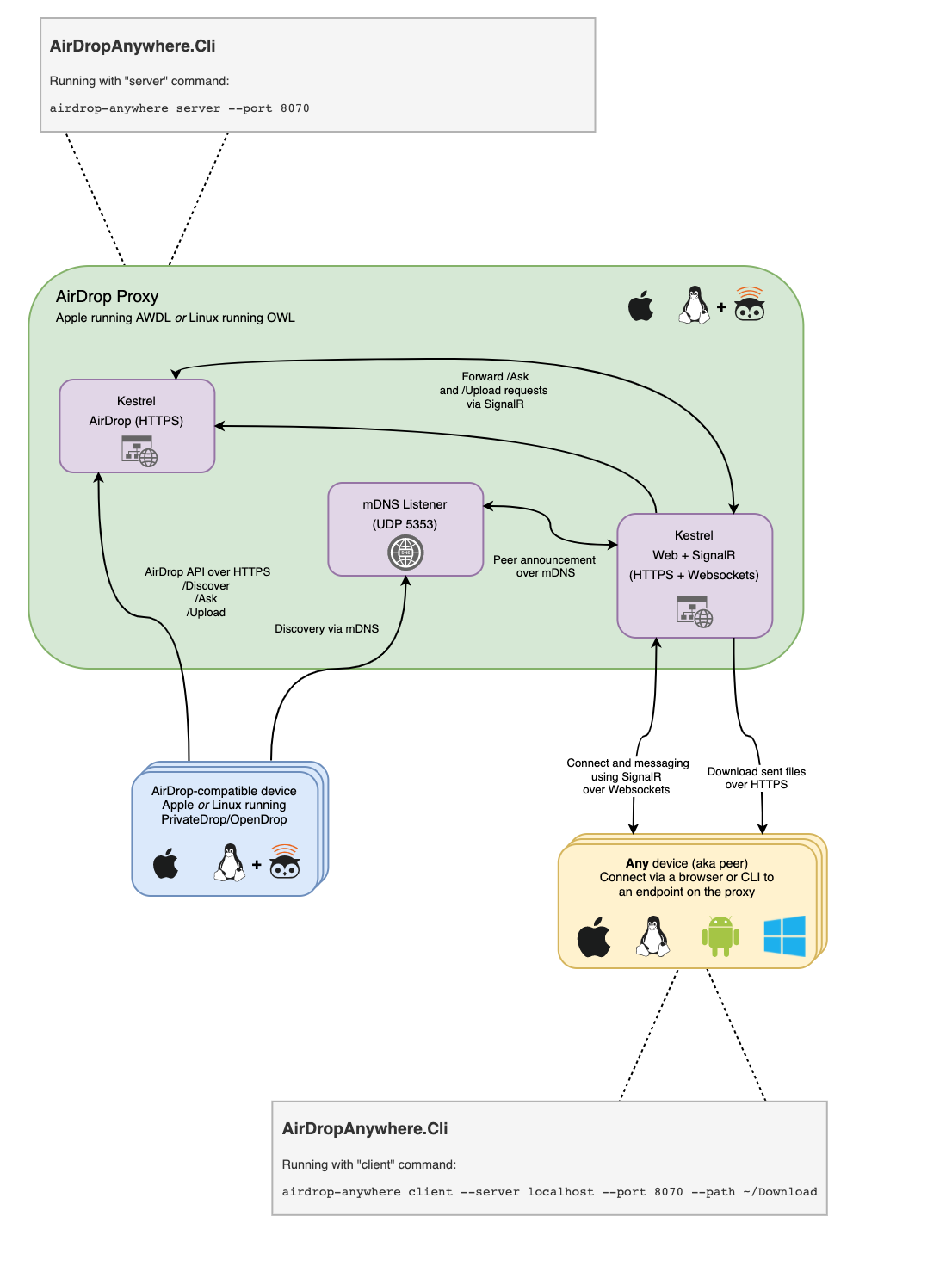

Initially I thought that splitting things into three projects was the sanest approach to building this - AirDropAnywhere.Core would contain the core parts implementing the AirDrop protocol with AirDropAnywhere.Cli containing the CLI components and AirDropAnywhere.Web containing a set of endpoints to support non-Apple devices. Instead I’ve decided to collapse hosting of all server and client pieces into AirDropAnywhere.Cli - this simplifies the build pipeline and provides a single executable that can act as either a client or a server to our AirDrop implementation. In practice this is implemented using the command support in Spectre.Console meaning the system now looks something like this:

AirDrop Anywhere System Diagram

Let’s run through some of the key concepts in the design and then dig into implementation details…

Peering Overview

In order to support non-AirDrop devices we need to have the concept of a “peer” - an arbitrary client that connects to our server and is made discoverable to AirDrop-compatible devices. This becomes a core abstraction in the code and the mechanism in which various subsystems communicate with each other. Say hello to AirDropPeer:

| |

This is fairly straightforward - there’s a unique identifier for the peer, a display name and some methods to allow the AirDrop HTTP API to communicate with the peer. This is implemented as an abstract class rather than an interface because we need to manage the identifier in the framework - we use this as the host name in mDNS and AirDrop is particularly fussy about what characters it allows in the hostname. We simply use a random 12 character alpha-numeric identifier which satisfies AirDrop’s requirements and means the implementor doesn’t need to know about this detail.

An implementation of AirDropPeer is provided by the underlying peering mechanism - in our case we’re allowing clients to connect using SignalR over Websockets so we provide an implementation that layers upon its messaging protocol. When a peer connects to our server we register it so that the core pieces in AirDropAnywhere.Core are aware of its presence. Similarly when the peer disconnects we unregister it. That functionality is exposed on AirDropService:

| |

These methods provide the surface area needed for the core pieces of AirDrop Anywhere to make a non-AirDrop compatible device discoverable. Let’s break down how this interacts with other parts of the code.

Registration

When registering a peer AirDropService creates an instance of MulticastDnsService using the Id property as the host & instance names. It keeps track of the peer in a dictionary keyed by Id. Then it tells MulticastDnsServer to announce DNS records for that service over the awdl0 interface - this is exactly what happened in the previous version of the code except we’re now dynamically announcing the existence of the peer rather than statically defining it. This announcement causes AirDrop to call the /Discover HTTP API using the hostname announced via mDNS - in our case the hostname is the same as the unique identifier of the peer.

AirDropRouteHandler has been modified to inject the instance of AirDropPeer associated with a request when it is instantiated - it does this by extracting the first part of the host header and performing a lookup using TryGetPeer. If that hostname resolves to an AirDropPeer then it continues executing the request as usual, otherwise it returns an HTTP 404. I say “as usual”, but what does that mean for each API in AirDrop?

/Discover- we’re currently operating in “Everybody” mode (instead of “Contacts-only” mode) so this API always returns details of the peer - notably itsNamefor rendering in the AirDrop UI./Ask- previously this always consented - now it makes a blocking call toAirDropPeer.CanAcceptFilesAsyncto allow the peer to decide if the operation should continue or not/Upload- previously this extracted uploaded files directly to the server’s file system. Not very useful! Now it notifies the peer of each file that was extracted and exposes that file to the peer via HTTPS to allow it to download it.

Unregistration

Unregistration effectively does the opposite of registration - it removes any trace of the peer in the server and announces it over mDNS with a TTL of 0 seconds. Announcing with a 0s TTL causes downstream mDNS caches to discard the records associated with the peer, making it disappear from any AirDrop browsers. Removing it from our server’s state causes any requests to the HTTP API to return a 404 because TryGetPeer does not return the peer anymore.

Peer Implementation

We’ve discussed how peering is intended to work, so let’s dive into the implementation details for peering using SignalR. Out of the box SignalR provides connectivity via Websockets with fallback to server-sent events or long polling (here is a good post on the differences between the transports), but it abstracts it all away using the concept of a “hub”. Clients connect to the hub and they can call methods on it or the server can call methods on the client - it’s a two way connection. Additionally we can implement streaming from the server to the client or vice versa.

There are some restrictions on the server calling the client - notably that the client is unable to return a response to the server. However, by implementing bi-directional streaming, we can layer a fully async request/response mechanism on top of SignalR’s streaming capablities. Consider a hub with the following method:

| |

This allows the server to send messages to the client (via the returned IAsyncEnumerable<T>) and for the client to send messages to the server via the IAsyncEnumerable<T> stream parameter. AirDropHubMessage generates a unique Id for each sent message, and a ReplyTo property containing the identifier of a message that the current message is in reply to. If ReplyTo is not set then the message is considered to be unsolicited.

When a client connects to the hub it calls StreamAsync and the server spins up a thread that is responsible for processing messages from the client’s IAsyncEnumerable. It uses a Channel<T> as the “queue” of messages produced by the server - as messages are posted to the Channel<T> they are yielded to SignalR which sends them over the connection to the client.

Callbacks

Under the hood the T used in our Channel<T> is actually a struct called MessageWithCallback that contains an AirDropHubMessage and an optional callback that is called if the message is in response to another message. Callbacks are handled by implementing IValueTaskSource - this is the ValueTask equivalent of using TaskCompletionSource and allows consumers of our SignalR implementation of AirDropPeer to await the result of an operation, even though that result is happening asynchronously on another thread (the one handling messages from the client). We keep track of the callback by storing a message’s unique identifier and the IValueTaskSource representing the callback in a Dictionary associated with the connection. When a message is received from the client we check to see if the ReplyTo property value is in that Dictionary and, if so, we invoke the callback with the message from the client.

IValueTaskSource is relatively easy to implement, there’s a struct in the runtime that implements the majority of its logic called ManualResetValueTaskSourceCore<T>, so our implementation, called CallbackValueTaskSource, simply wraps it:

| |

When a reply message is received, and we’ve found a callback, we simply call SetResult(AirDropHubMessage) with the message. If a caller was awaiting a ValueTask that wraps the IValueTaskSource it’ll resume execution.

It’s important to note the Reset method on this class - in order to minimise allocations we use an [ObjectPool(https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/aspnet/core/performance/objectpool?view=aspnetcore-5.0) to keep a few instances of the class around for re-use. When we want an instance we call ObjectPool.Get() to get one, use it and then return it to the pool when we’re done. Reset allows us to safely re-use that instance later.

That’s a lot of words! Let’s take a look at how that works when implemented in the SignalR peer (note: code has been delibrately simplified for the post):

| |

This might seem a little convoluted but it allows us to have a pretty useful request/response implementation over the top of a full duplex stream between our server and client. Importantly, the core pieces don’t need to know any details on how messages are relayed to the peer, they just await the call.

Polymorphic Messages

By default SignalR uses System.Text.Json to serialize/deserialize messages across the wire. Usually that works just fine but here we’re using bi-directional streaming with the abstract base class AirDropHubMessage. System.Text.Json has no idea how it should handle derivatives of this type so we need to give it a helping hand - enter PolymorphicJsonConverter. This JsonConverter reads and writes JSON associated with the concrete type of the object but wraps it in a named field so that it knows what runtime Type to deserialize to. We then add attributes to AirDropHubMessage that teach the converter which mappings it should handle:

| |

When serialized the JSON looks like this:

| |

When deserializing the connect key is used to lookup the right runtime type for the message - in this case ConnectMessage is used. This lets us maintain our simple streaming signature using IAsyncEnumerable<AirDropHubMessage> but allows us to pass any derived type to and from the connected parties.

Uploading files

I mentioned above that our previous implementation of AirDrop’s /Upload API just extracted files to the server’s file system. Now that we can relay things to a peer we can forward arrays of bytes representing chunks of a file to them directly, yay! Unfortunately the story doesn’t end there - if we connect to our SignalR server using a browser then our options for handling the array of bytes are somewhat limited - we need to construct a Blob and once we have all the chunks we can use some creative hacks to get the browser to trigger a “download” to the user’s local machine. Except that we’ve already sent the bytes to the client so, in the case of large files, it’s quite possible that the Blob is backed by memory or temporarily buffered somewhere else, likely with some kind of limits to prevent abuse.

Instead I’ve added a StaticFileProvider to the Kestrel instance spun up in the AirDropAnywhere.Cli server instance that maps to an uploads directory on the server. When we extract uploaded archives we generate a new directory here and new files are added to it. Once the archive is extracted we notify the client of each file that was extracted and its corresponding URL on the server - once the client has successfully downloaded all the files it needs then those files are removed from the server.

This allows us to stream the files directly to the client’s browser without any unnecessary buffering along the way - it’s a trade-off - we’re expecting the server to have storage space to extract any archives sent its way but we can rely on the client’s ability to download things directly rather than using semi-supported workarounds with Blob and File in the browser.

Glueing it all together

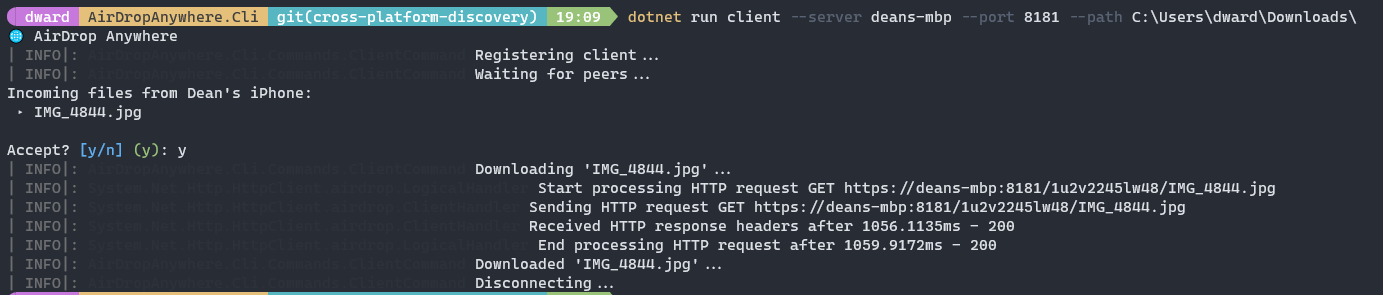

Now we have a (relatively) sane approach to peering we can implement our first consumer. This first consumer will run at the command line and it’ll perform the following steps:

- Connect to an AirDrop Anywhere server using SignalR and immediately send a

ConnectMessagecontaining the peer’s name.- Once connected the server will announce the peer over mDNS.

- AirDrop will discover the peer via this announcement and call the

/DiscoverAPI over HTTPS.

- Wait for a

CanAcceptFileRequestMessagefrom the server. This is sent when a contact is tapped in the AirDrop UI, triggering a call to the/AskAPI over HTTPS.- Once received, the CLI displays a prompt to the user asking if they want to accept the files being sent.

- If they hit, Yes then continue, otherwise go to 2. Either way, return the response as a

CanAcceptFileResponseMessageso the server knows to how to continue.

- For each file, receive a

FileUploadedRequestMessageand use the URL within it to download the file from the server.- Once the file is downloaded, send a

FileUploadedResponseMessageto acknowledge receipt.

- Once the file is downloaded, send a

All of this logic is wrapped up in ClientCommand in the AirDropAywhere.Cli project. This makes use of Spectre.Console’s wide array of formatting options to render the prompt and show output from the file download process.

There isn’t anything particularly “magic” in this implementation - it is a simple SignalR client that renders some UI and uses an HttpClient to download files. The only quirks are ensuring that we ignore certificate validation errors when connecting over HTTPS for downloads or with SignalR - when running on a different machine the default ASP.NET development certificate is not trusted and therefore fails validation. Eventually I’ll implement a certificate generator and change the validation to ensure the certificate is generated from a specific well-known root to eliminate the risk of MITM attacks.

We should be able to take the same structure used here and trivially apply it to a client implemented in JS or Blazor running entirely in the browser.

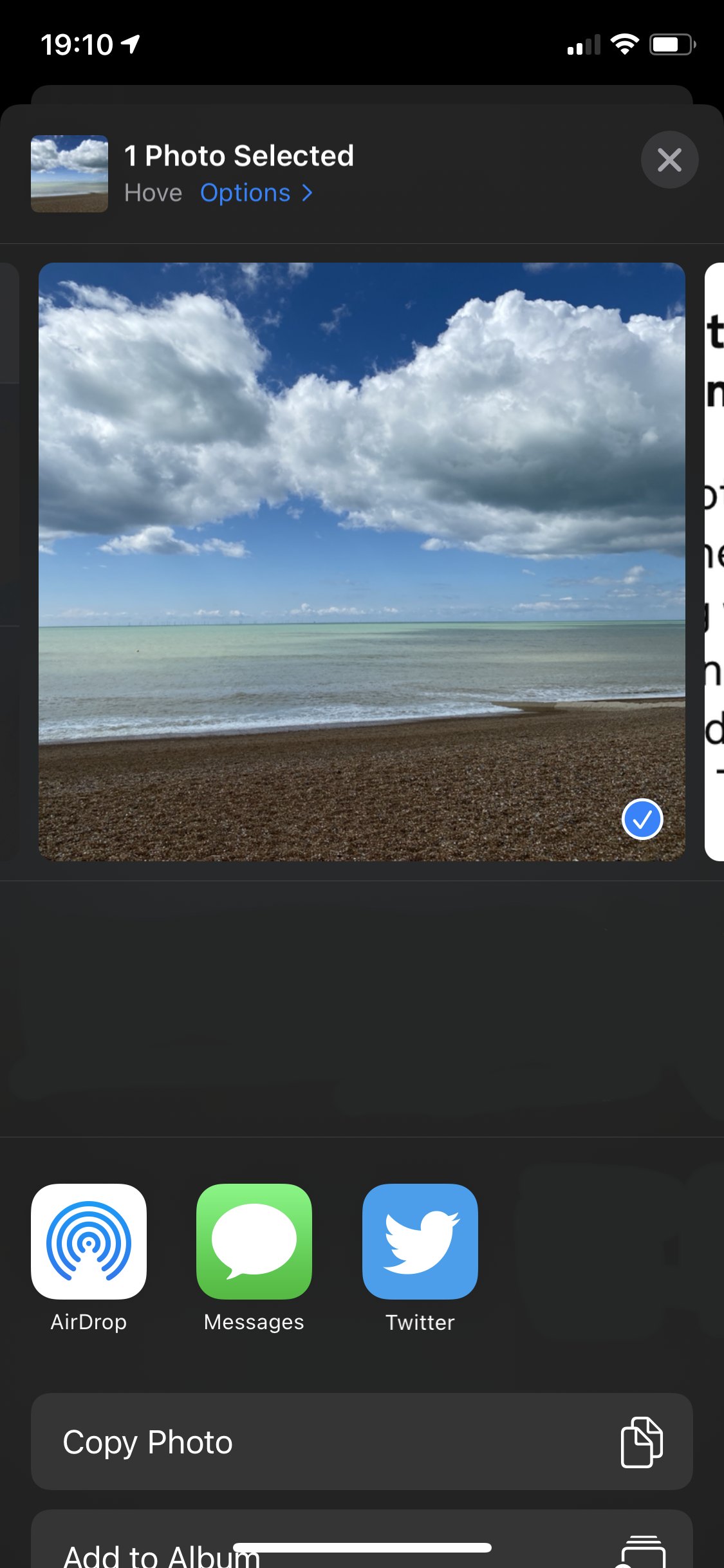

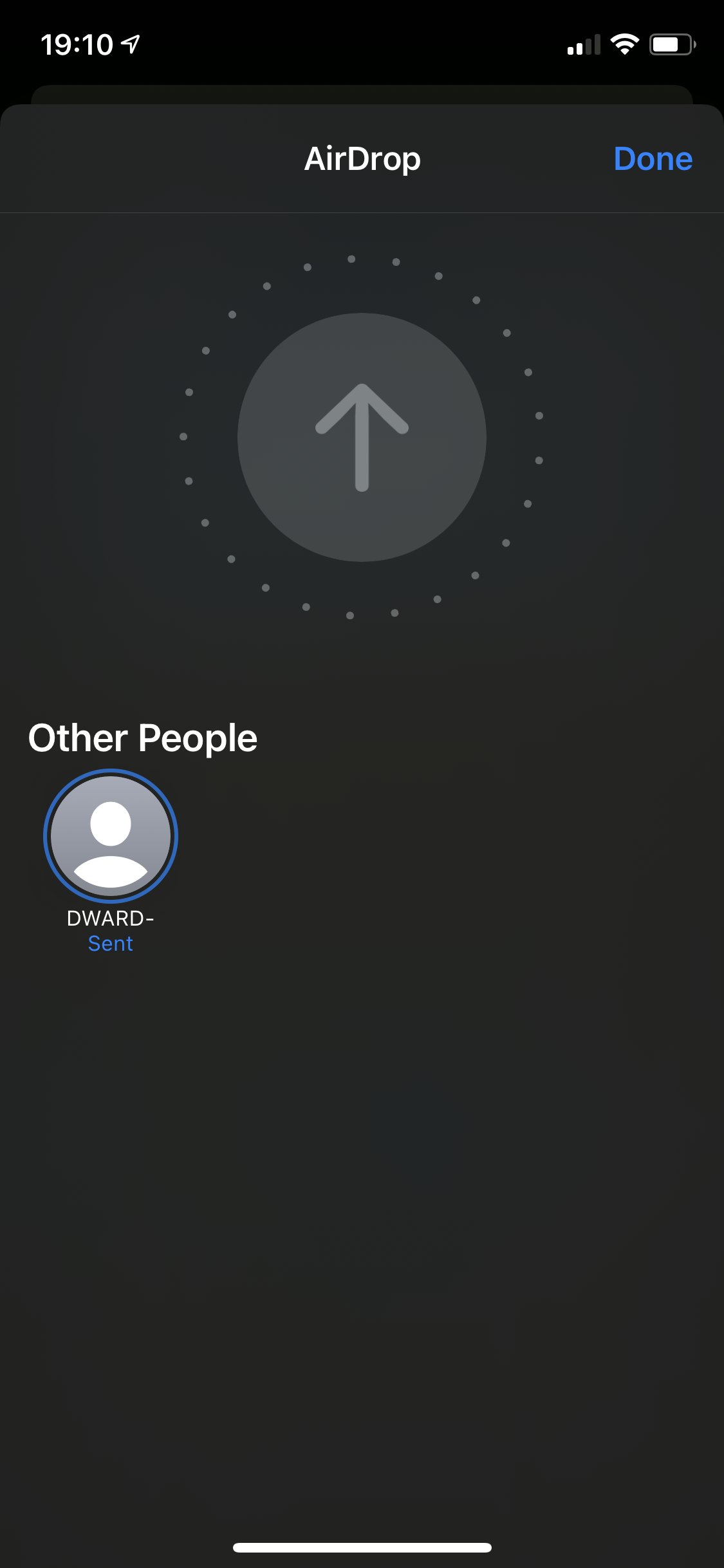

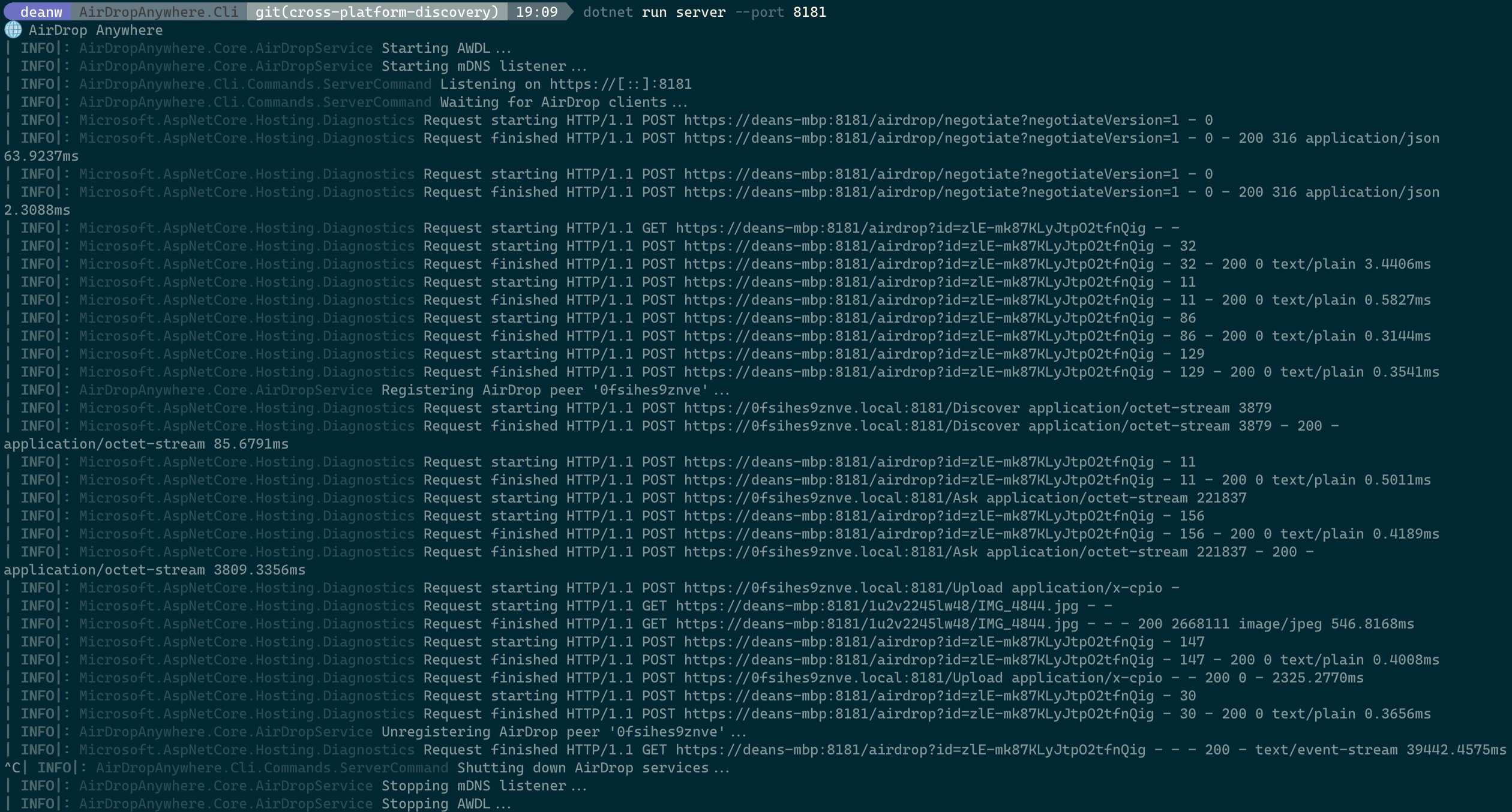

Here’s a rough view of how it looks so far - this is the journey from iPhone to a Windows desktop via a Macbook Pro:

|  |

| Sent from iPhone... | ...via macOS... |

| |

| ...to Windows! |

Next time

Next up, I’ll be implementing the client to have all of this running entirely in the browser. I’ve put together a list of things I plan to work on over the coming weeks in a GitHub project in the AirDropAnywhere repo.

I’ll likely be moving the project to use .NET 6 in the very near future. In my last post I detailed a workaround for allowing Kestrel to accept connections on the awdl0 interface by adjusting the listen socket’s options. Thanks to Sourabh Shirhatti at Microsoft an issue was created in the ASP.NET Core repo and I was able to add support for customising the creation of Kestrel’s listen sockets directly to ASP.NET - this eliminates the need for my workaround altogether 🎉!

The end goal of all of this is to publish an executable that can be run on any device supporting AWDL or OWL (Apple or Linux with an RFMON-supporting wireless interface) as a daemon providing AirDrop services to a home network (I suspect this wouldn’t scale to anything larger than that 🤔). Additionally I’d like to have AirDropAnywhere.Core published as a NuGet package that would allow AirDrop to be consumed by things like GUI applications, potentially allowing arbitrary files to be “dropped” to any application on any (supported) platform! Stay tuned!