This is part 3 of a series of posts:

In the previous episode we talked about the challenges I came across while implementing the mDNS advertisements necessary to support AirDrop. By the end of this episode we should be able to send a file from an Apple device to another Apple device running our service 🎉.

How it works

From last time - AirDrop works by advertising the endpoint associated with an HTTPS listener. Right now we don’t have anything listening for requests - so we’ll need something listening on HTTPS and have it implement the relevant API routes that AirDrop expects. To do so we need to know what the API surface looks like!

Typically to reverse engineer an API implemented over HTTPS we’d use something like Fiddler to intercept HTTPS traffic and decrypt it, but because AirDrop configures an ad-hoc connection over the AWDL interface, we don’t have anyway to force it to route traffic via Fiddler. Our next option is to use Wireshark on the AWDL interface and configure it to decrypt TLS. Fortunately, AirDrop supports self-signed certificates for whatever is listening on the HTTPS endpoint - so we can trivially use the ASP.NET Core Development Certificate stored in the keychain and configure Wireshark to use it. Then all we need to do is sniff packets on the listening device’s AWDL interface…

However, other than for monitoring what’s going on, we don’t need to do this to work out the API surface! PrivateDrop and OpenDrop both provide an implementation of the API that we can translate to the equivalent C#.

API Endpoints

AirDrop needs 3 endpoints in order to function:

/Discover- accepts a POST containing information about the sender of the request and expects a return message containing details of the receiver such as its name and capabilities. This route is called immediately after an mDNS request returns the details of our HTTPS endpoint./Ask- accepts a POST containing information about the sender and metadata on files it wants to send. This route is called when the user clicks a recipient in the AirDrop UI and is expected to block until the receiver has confirmed that they want to receive the files./Upload- called once the sender has been authorised to send files. It performs an HTTP POST containing the files’ data. What format those files are in depends on capabilities returned by the call to/Discoverand the flags contained in the TXT record advertised using mDNS.

Spinning up the server

Exposing the HTTPS endpoint we need is as simple as spinning up an instance of Kestrel and having it listen using the default development certificate. Using that certificate is a little hacky but it works and we can generate our own self-signed certificate later.

This code is heavily cutdown for the blog, but it effectively looks like this in the AirDropAnywhere.Cli project:

| |

ConfigureAirDrop is an extension method on IWebHostBuilder in the AirDropAnywhere.Core project - eventually we’ll allow any application to expose AirDrop by consuming the Core project as a NuGet package which is why it’s structured like this.

| |

This is pretty simple - it configures Kestrel to use HTTPS, for it to listen on any IP address and use endpoint routing. We expose some options that allow us to configure things like the listening port and then call down into extension methods that add relevant services and map the API’s endpoints:

| |

You’ll see that we add an IHostedService called AirDropService - this is what handles our mDNS advertisements and sets up AWDL on macOS. IHostedService exposes a StartAsync and StopAsync that allows us to tie the lifetime of our service to the underlying WebHost which makes it perfect for long-running services.

Then, we add some POST endpoints to endpoint routing and have them hook into AirDropRouteHandler. ExecuteAsync simply does some boilerplate bits per request - it spins up an instance of AirDropRouteHandler and then calls an instance method to do the work of handling the request.

It’s possible that just moving this to WebApi or MVC would be a better long term bet, something to consider for a future refactor.

But does it work…

After spinning up the application, sniffing the AWDL interface using Wireshark and gleefully opening AirDrop on my iPhone it… doesn’t work. Well, pants 🤦♂️. Wireshark indicated that opening the connection to the HTTPS endpoint fails with a timeout. I gave this a little thought and quickly realised that it was for the same reason that my mDNS implementation failed the first time around - I need to explicitly tell the OS that this socket needs to use the AWDL interface. Easy peasy!

Well, I thought that would be the case - surely Kestrel has trivial extensibility points to mess with its underlying sockets? Turns out that isn’t the case at all. Kestrel uses an implementation of the IConnectionListenerFactory interface called SocketTransportFactory. This is responsible for binding to the underlying transport and returning an IConnectionListener. I don’t particularly want to implement all the plumbing that SocketTransportFactory does and, unfortunately, all of its internals are, ummmm, internal.

Reflection to the rescue! Yes, this is terrible practice but it gets me where I need to be so I’ll take it. Here’s what I came up (again, abbreviated for the blog post - you can see the actual implementation here);

| |

We can tell Kestrel to use this by updating our AddAirDrop extension method to use the service, but only on macOS:

| |

And… it works! AirDrop successfully POSTs a message to /Discover and we promptly respond with a 200 OK. Naturally this doesn’t make the sender do anything, but it’s a start!

/Discover

Reading the request

Upon inspection of the POST body sent to /Discover we see something like this:

| |

What the heck is this? Content-Type is set to application/octet-stream and, based upon the first few bytes of the payload, it turns out to be a binary-encoded plist. Plist is a format commonly used in the Apple ecosystem but, seriously, wtf - why on earth anybody would use this in an HTTP API is beyond me - it’s wildly verbose, even in its “binary” representation - look at all the frickin’ XML!

Fortunately a few people have gone to the bother of implementing plist for .NET - I picked plist-cli because it seems to represent things in a coherent way. That said it materializes things as a set of NS* instances rather than, say, a POCO (plain ol’ CLR object). Ideally I want to materialize this payload as a POCO for easier consumption downstream. I ended up writing a few wrappers that take the raw request body, deserialize it using plist-cli and then uses some more reflection nastiness to bind it to a POCO. Similarly, for responses it does everything in reverse - translates the POCO to something plist-cli understands and then lets it take over serialization to the wire format. My intent is to replace this with something that reads/writes plist directly from the POCO, probably using some source generator fun but, for now, what I have works. See the Serialization namespace for the code that handles all this.

A couple of extension methods add support for reading / writing the plist format from the HTTP request / response:

| |

Now we can read the thing that AirDrop sent us, let’s see what we can do with it!

Understanding the request

This payload represents a set of information that the sender knows about - notably the hashes of the sender’s email address and phone number. This is used by AirDrop in “contact-only” receive mode to see if it knows the sender and allows the receiver to determine whether it should “expose” its details to them.

Contact information is embedded within the plist we received above as an NSData instance - effectively a binary blob. It turns out it’s a PKCS7-signed payload, signed with Apple’s root CA. .NET Core gives us the SignedCms class to validate PKCS7 signatures. To use it we need a copy of Apple’s root CA public key which we can extract from KeyChain or, easier, just grab directly from PrivateDrop and embed it as a resource in AirDropAnywhere.Core. Here’s the code to validate the payload (taken from DiscoverRequest.cs):

| |

This ends up giving us a POCO containing the sender email and phone hashes that we can use for validation:

| |

Right now, I’ve decided not to implement “contacts-only” mode so we don’t need this - yet! I will implement that part later - for the moment I’m more interested in actually receiving a file.

With that in mind, we’ll validate that the data is legit (by calling TryGetSenderRecordData) but we’ll simply return the /Discover response - a payload containing our details - the name of the receiver and its capabilities:

| |

Capabilities

A receiver can indicate to the sender what types of media it is capable of receiving in the response body. Typically this lights up more advanced formats such as the High Efficiency Image Format, but I don’t intend to support these. I have no idea if the underlying devices I want to use AirDrop with can support receiving these kinds of files so we return simply indicate that we do not support any capabilties - effectively dumbing down the media to its most compatible format.

This is expected to be provided as the UTF-8 encoded bytes of a JSON payload inside of our binary-encoded plist. Honestly, can this get any worse?

And the result…

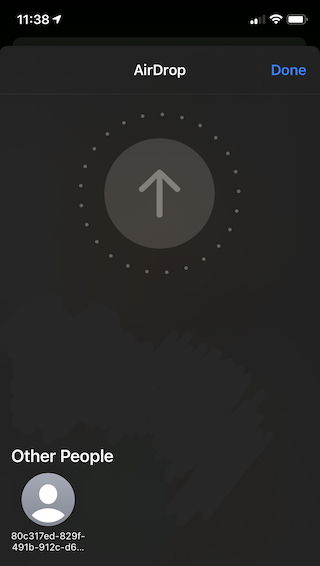

After implementing this endpoint we can see that AirDrop now “sees” our service, GUID and all. Hooray!

It’s Alive!

Next, we need to see if the receiver wants to receive the files we’re sending…

/Ask

This is a relatively simple API - it’s called when a user taps our icon in the UI and is intended to block until the receiver decides whether or not they want to receive what we’re sending to them.

Again, it’s a binary-encoded plist that I’ve mapped to the following POCO:

| |

There’s a fair bit in the request, but the tl;dr is that it contains some metadata about the sender and about the files that they are sending to us. As we start to implement the clients that do not natively support AirDrop we’ll need to implement this endpoint properly but we can get away with returning an HTTP OK with the following response in binary-encoded plist format:

| |

/Upload

This is the endpoint that AirDrop calls to actually transfer files from sender to receiver. As soon as we confirm the /Ask request AirDrop immediately calls this endpoint with a POST body containing the files we asked for. However, as with the rest of this API there’s some quirks under the hood.

When we advertise our instance of AirDrop using mDNS we provide a TXT record called Flags that contains a bitmask of the following flags enum:

| |

These were all derived from the work performed by Secure Mobile Networking Lab in their OpenDrop and PrivateDrop implementations. By default macOS broadcasts a bitmask value of 1019 which corresponds to Url | DvZip | MixedTypes | Unknown1 | Unknown2 | Iris | Discover | Unknown3 | AssetBundle. This value is interpreted by the sender of files and is used to ascertain capabilities of the receiver. Sounds a bit like the media capabilities thing doesn’t it? I’m unsure why these are split, but I suspect that it’s possible that /Discover came after this implementation (a wild guess based upon the presence of the Discover bit in the enum above).

One of these flags is the DvZip bit - this indicates what format the POST body to /Upload is in. When this bit is present we get an opaque binary format that the file command cannot understand and none of the tooling on my Mac seems to understand either. It appears to be totally undocumented :(. When it’s not there then we get a different file format - judging from OpenDrop it appears we’re dealing with an OIDC encoded cpio archive. This format consists of a stream of “records” each containing a header with metadata about the data following it:

| |

OIDC is an ASCII format and each of the fields in the struct are represented as an octal string. namesize and filesize indicate the size of the filename and data following the record. The stream of records ends with a record that points at the filename TRAILER!!!. Once we hit this we know we’ve successfully parsed the contents of the archive.

To test this I saved an uploaded archive directly to disk and poked at it with cpio but I couldn’t get it to extract. Finally, after banging my head against the wall for a while I ended up running file which prompt told me that the archive was also GZIP compressed. I completely missed this because AirDrop doesn’t bother to set the Content-Encoding header on the request, ya know like the spec says 😡. After running gunzip the cpio command works perfectly and I can extract the files sent over AirDrop successfully!

Now to implement this in C# - there’s a few implementations used for extracting CPIO archives on NuGet, but none of them really play well with the async-only bits of the HTTP pipeline in .NET Core. I really want to extract directly from the stream (something that cpio’s format is great for) and many of the NuGet packages expect to operate on the file system. Instead I wrote a streaming extraction that understands (only) OIDC format archives and interfaces with the PipeReader from an HttpRequest. When coupled with a GZipStream to decompress as we go the endpoint can now successfully extract uploaded files to a temporary directory. CpioArchiveReader is a little lengthy to breakdown here so you can see the code here.

The most difficult thing about that implementation is grokking how PipeReader works but Marc Gravell has a good set of posts that I used as a primer and he also graciously spent some time to help me understand what the hell I was doing there. Thanks Marc!

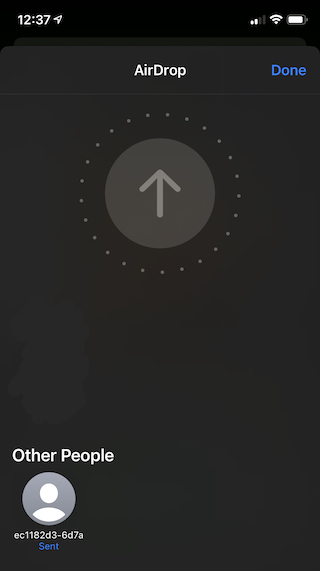

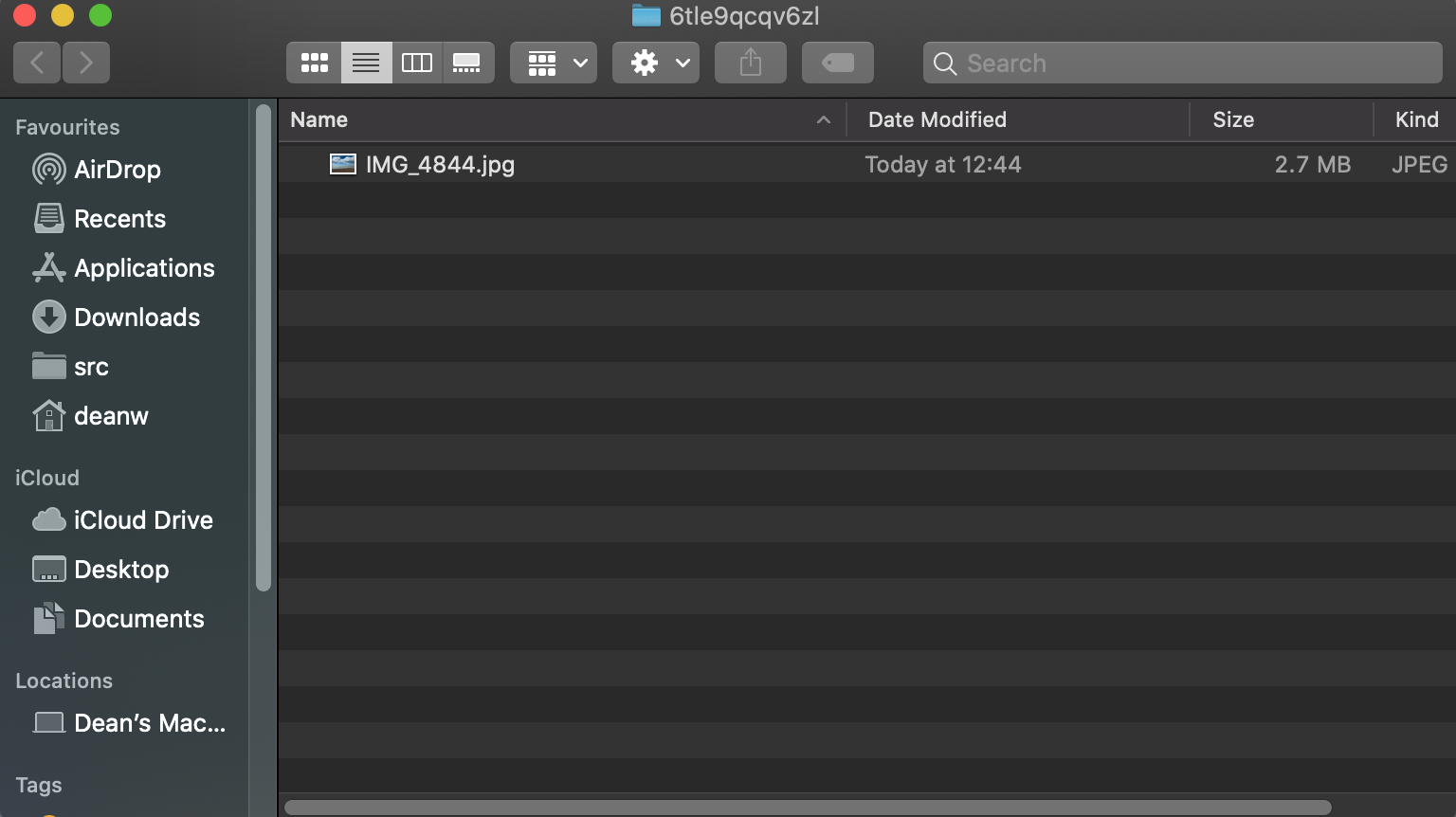

But, does it work?

Yes, it does! I sent a few files (both individually and as a “bundle”) and they get successfully decompressed and extracted to the file system 🥳. While this is next to useless for actual consumption (files are written to a temporary directory in this version), this is an important first step to hooking up non-native AirDrop clients to the proxy.

|  |

| Sent from iPhone... | ...to macOS |

Note that the current implementation is a security nightmare - it effectively allows any AirDrop device to blindly send files and have them stored on the target device. We’ll need to address these shortcomings before running this proxy on anything that isn’t just used for development!

What’s next?

Now we have the ability to receive files from an Apple device our next task is to define the interface that allows non-native clients to be discovered via our proxy. Next time we’ll dig into what that interface looks like and how we’ll hook it up so we can use it via the CLI and an internally hosted site. Enjoy!