After a whole lot of months in the making we finally finished porting Stack Overflow to .NET Core 3.1 🎉! When you hit any part of Stack Overflow or the wider Stack Exchange network you’re now hitting our main application running on .NET Core behind IIS using the in-process execution model. We plan to have a whole series of blog posts about the port - the good, the bad & the ugly, but today I’m going to focus on how the move to .NET Core has allowed us to have greater flexibility in our local development environments

Generally speaking our developers and designers use the following environment to build and run the Q&A application:

- Windows 10

- IIS

- Visual Studio 2019

- Redis 4.x

- Elastic 5.x

- SQL Server 2019

All of this is installed on bare metal or a VM running under Parallels on MacOS. As I’ve mentioned before we have a set of scripts called Dev-Local-Setup that we use to make this installation process easy and repeatable - but those scripts only work on Windows… until now! This post is about the journey to running on MacOS for day-to-day development; from making sure our application runs well there to inventing viable replacements for things like IIS.

Building on MacOS & Linux

Before we could get our setup scripts running on non-Windows platforms we figured it would be helpful if the application we were trying to run worked on those systems too!

Don’t be so sensitive!

One of the first things to overcome was the many places that we had incorrect casing or path separator assumptions in our code, tests, build scripts or DB.

It’s probably worth mentioning that, depending on the file system you use on a Mac it might be case-sensitive! Recent versions of MacOS use a case-insensitive file system; that took me a little by surprise - I had done most of the casing changes on MacOS and then a bunch of additional things broke when I tried the build on Ubuntu!

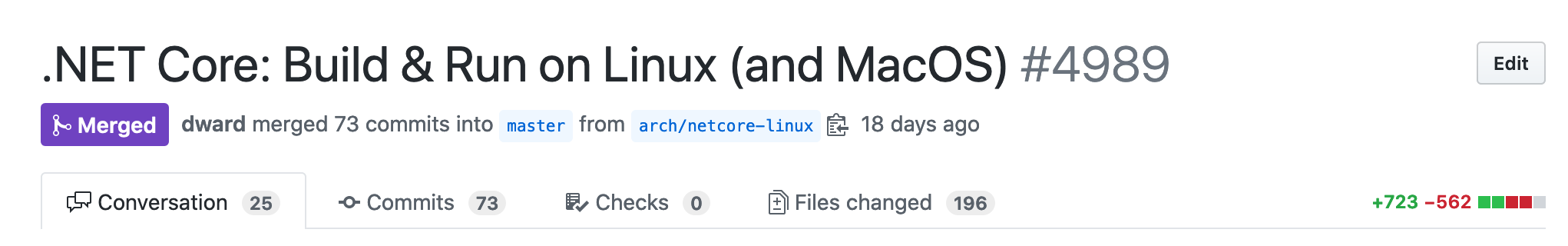

Years of case-insensitive file systems meant we had accumulated a fair number of broken paths - appSettings.json should have been appsettings.json, /content should have been /Content, lots of \ separators. Fortunately they were easy, if not a little repetitive to fix - mostly a case(!) of find/replace. That was a good chunk of this PR;

.NET Core: Build & Run on Linux (and MacOS)

But, that wasn’t the only thing that needed addressing though, next up…

Binary Dependencies

During our builds to dev & prod environments we prepare all our client-side assets for deployment. That process compiles our LESS stylesheets into CSS, performs minification and bundling of CSS & JS and minifies images. To do all of this we run a node.js script to do the heavy lifting; a lot of the tooling for dealing with JS & LESS works best with node so we use the best tool for the job! Unfortunately, in order to run the script we had a node.exe binary committed into the repo (we have different versions of node used across projects and it’s easier to manage the versioning if the dependency is local to each project). Sadly that doesn’t play too well on non-Windows systems :(

To workaround that we used the handy Node.js package on NuGet. This package is a massive blob of node binaries for Windows, MacOS & Linux. Sounds like a terrible idea, doesn’t it? But it has a couple of big advantages; 1. it means we don’t have to commit the binaries into source control (yay for package restore!) and 2. it means we can delegate all platform-specific decisions to MSBuild and the NuGet targets - it knows what platform we’re on and makes sure we get the right tooling directory.

To optimize this a little further we can also make sure the massive package is only retrieved for builds that need to compile client-side assets - that’s something we don’t usually do anywhere but a build server. That means local development environments don’t need to download the package at all.

Now we have that package we can simply run the right binary for the platform, passing in our script and its parameters as usual.

Long term compatibility

Now that we have the application building and running on multiple platforms we wanna make sure it stays that way. To achieve this we’ve provisioned Linux agents running CentOS (which is what we run for production services like Redis & Elasticsearch) that run build checks on PRs - those checks do things like compile the application, compile client-side assets and run unit / integration tests. If these builds break then the PR can’t be merged into master.

Longer term we’ll be spinning up ephemeral Windows & Linux environments that will be running the code from a PR so that we can smoke test things as well.

For the foreseeable future Stack Overflow and the other public sites will continue to run on Windows & IIS but we want to make sure we have the ability to run on Linux for our Enterprise customers and on MacOS for our own local development needs.

Configuring the local environment on MacOS

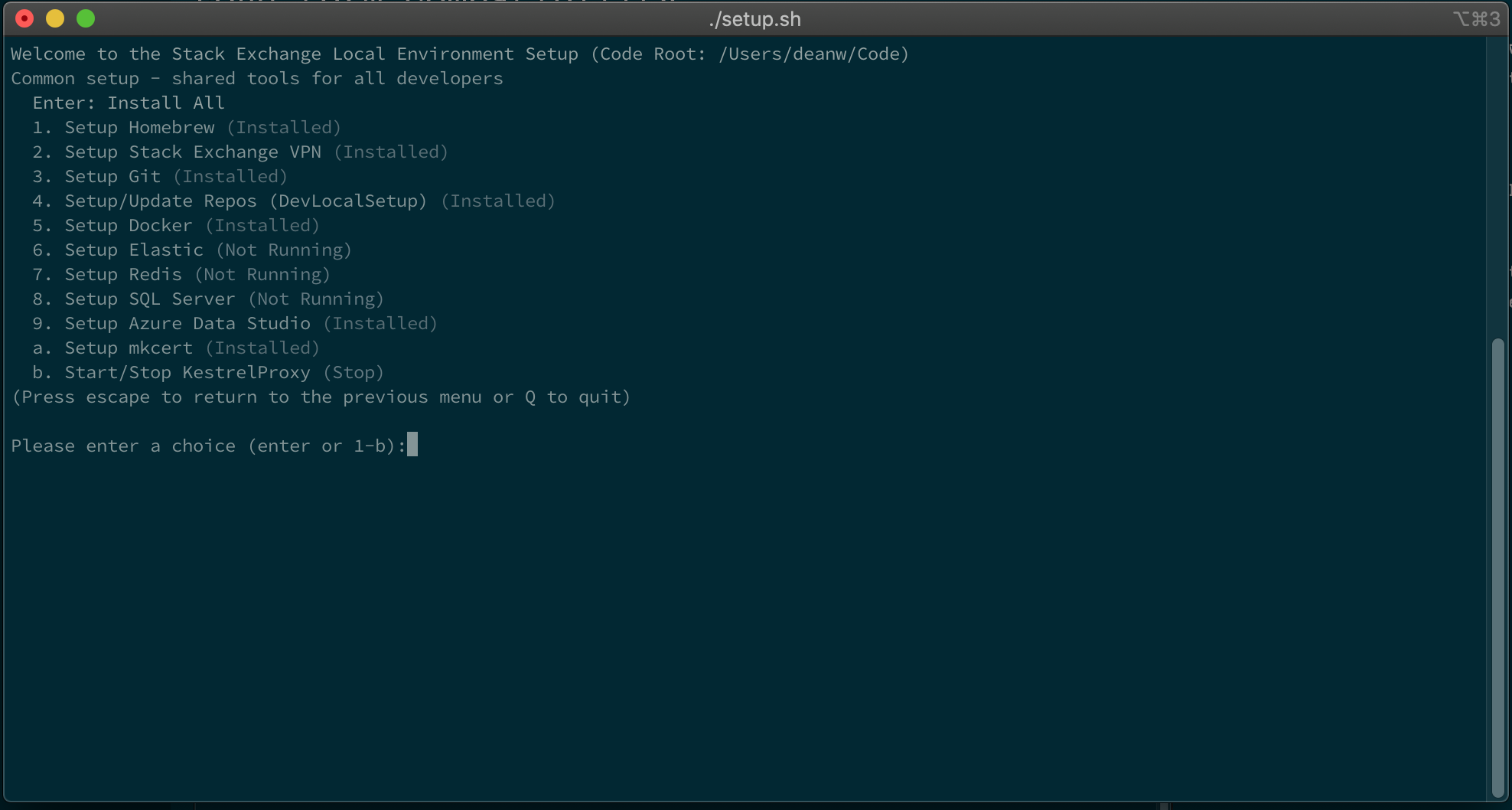

Dev-Local-Setup on MacOS

Once we had confidence that the application could run on non-Windows platforms we got to work on our setup scripts. There’s a bunch of things that our Windows environments give us that we either have to emulate, replace or change our strategy for on MacOS;

- Powershell; we don’t really want to maintain two completely separate sets of scripts forever.

- IIS; we could use nginx as a reverse proxy, but IIS does nice things like process management for us when using the ASP.NET Core hosting module - can we do something similar?

- Certificates; we generate self-signed certificates - is there an equivalent process on MacOS?

- Package management; we use Chocolatey on Windows - Homebrew seems like the most viable alternative here

- Redis/Elasticsearch/SQL; we install these directly on Windows - using Docker seems far saner on MacOS

Bootstrapping

MacOS doesn’t have Powershell installed out of the box (surprise!), so we need to make sure we have the bare minimim of pre-requisites to bootstrap our scripts.

We know that we have the ability to run shell scripts out of the box so our bootstrapping process consists of a setup.sh that does the following;

- Makes sure we’re running as

root. I’m not particularly fond of this, but most of what we’re doing during setup needs elevated access and this helps eliminate password prompts when installing a bunch of things unattended - Installs the .NET Core SDK, or updates it if we need a new version. This uses the

dotnet-installscripts from Microsoft - Installs Powershell Core using

dotnet tool install --global. This gives us access topwshacross the system - Makes sure the environment is generally in a sane state; making sure paths are valid, that we have an SSH key for connecting to GitHub, etc. We need most of those things before we can run the main scripts.

Once all that is done we can start our main Powershell script!

Supporting MacOS

Powershell Core has a few variables that allow us to check what platform we’re running upon - $IsLinux, $IsWindows, $IsMacOS. We’ve added support for conditions in our menu system in Dev-Local-Setup and this allows us to filter what menu options are available based upon the platform. There’s no sense in exposing “Install Homebrew” on Windows when we use Chocolatey! In addition we can now branch on those variables in menu items that should work cross-platform to do platform-specific things - e.g. we use this to change paths based upon the platform or do things like use the Registry on Windows rather than a config file on *nix.

It’s worth noting that on Windows with regular old skool Powershell those same variables are not available. To make sure our scripts run everywhere we can define $IsWindows as follows;

| |

Redis/Elasticsearch/SQL

On Windows we install our service dependencies directly on the machine. Using Docker feels far more sane on MacOS and, frankly, we’ll probably use the same approach on Windows in the coming months now that Docker has shipped native support for WSL2.

For now, we’re using Homebrew on MacOS to install the Docker cask then tweaking the Hyperkit VM settings JSON (~/Library/Group Containers/group.com.docker/settings.json) to give more RAM, disk and CPU cores to Docker.

Once that’s done we have several docker-compose files that construct containers for Redis, Elasticsearch and SQL Server that roughly mimic how our production environment looks.

For Redis we run all our instances in the same container and orchestrate their lifetimes using supervisord. Thanks to ejsmith for this PR to StackExchange.Redis for that approach, it’s awesome - it means we get all the logs in one place and just one container to spin up for all our Redis services!

For Elasticsearch we install the base container from Elastic and add the ICU and kuromoji plugins; we need those for our international Stack Exchange sites.

For SQL Server we use the example for configuring a non-root instance from Microsoft to install SQL 2019 combined with the example for configuring full-text search. We need the latter for efficient text queries across a couple of our tables in production and this keeps our local environments consistent.

SQL Authentication

On Windows we configure our applications to use integrated authentication to connect to their SQL databases. We grant DB permissions directly to the IIS application pool identities (i.e. the IIS APPPOOL\{AppPoolName} pseudo-accounts). This is similar to how we run in production - an application pool runs in IIS as a specific AD user and we grant DB permissions to that user.

On SQL Server for Linux we’re unable to use integrated authentication so we have to use SQL authentication instead.

When we initially build the container for SQL we generate a random, secure password for the sa user and store it in an environment variable that can be used by scripts or from the CLI.

When an application is configured from Dev-Local-Setup we use the host header that the application is exposed from as the user id and generate a password that is salted based upon the sa password.

By default, in an application’s appsettings.json we usually use a connection string that uses integrated authentication but we need to override this on MacOS. To do so we use environment variables with a specific prefix, hooking into the configuration provider model that is used in .NET Core - I’ll dig more into the specifics of that later on!

SQL Tools

In the absence of SSMS on MacOS we’re installing Azure Data Studio - it’s not quite at the level of SSMS yet, but it handles the majority of day-to-day tasks against SQL really well.

“Replacing” IIS

In production we have a shared web tier running a number of applications - there’s Q&A, API, Talent, Chat and other supporting services. HAProxy TLS-offloads traffic to a server running IIS and we use host headers to route the traffic to the right application pool.

We want our local development environments to reflect this as much as possible, but in the absence of IIS we’re somewhat limited in our options.

In IIS the ASP.NET Core Hosting Module manages the lifetime of our application by spinning up dotnet for us either out-of-process or in-process (the model we use; it’s faster). When somebody hits the host header associated with the application IIS makes sure there’s something running that it can route the request to.

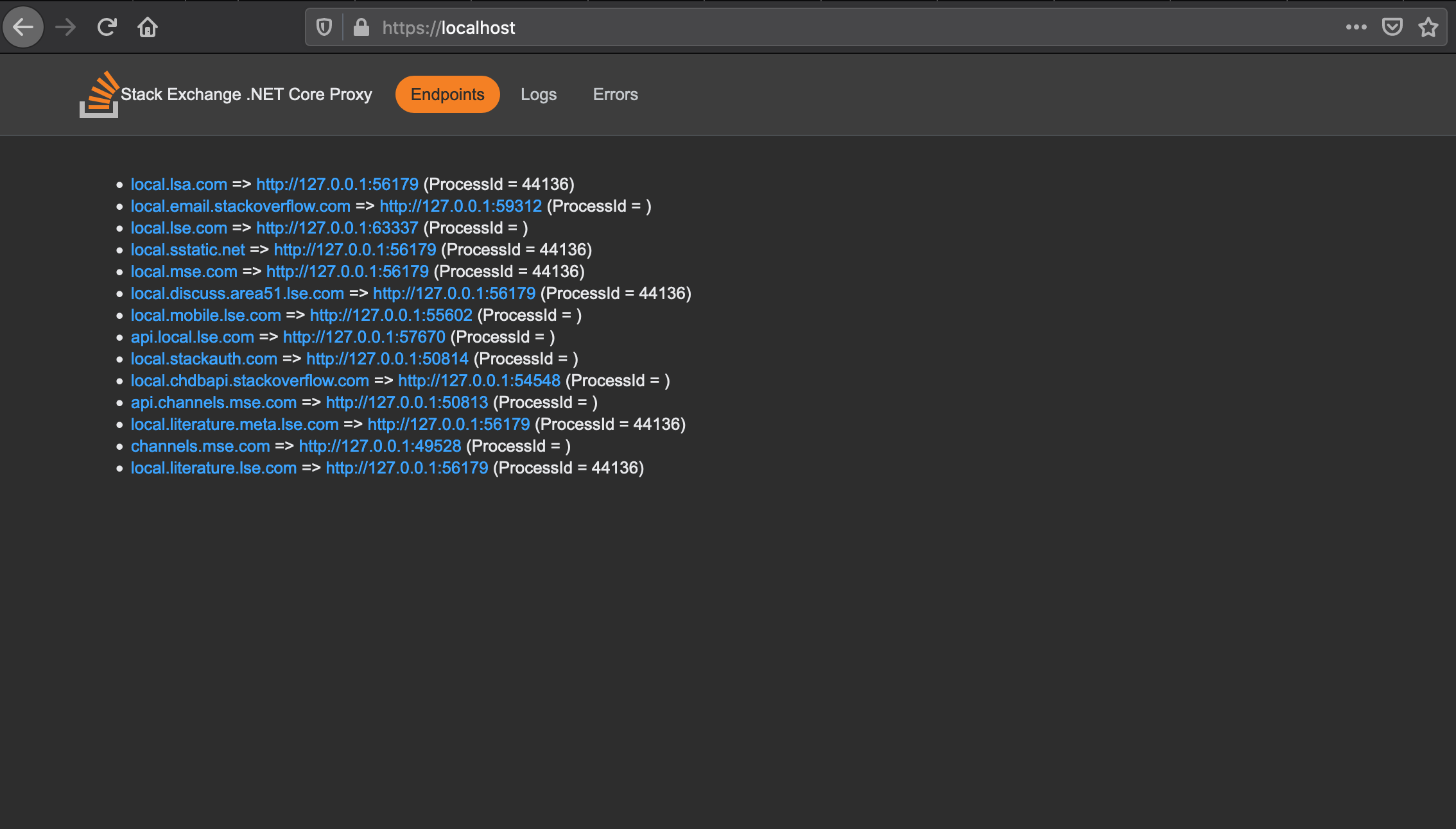

On MacOS we considered using something like nginx to reverse proxy inbound requests based upon the host header, but we couldn’t find any way to trivially manage the dotnet process that is actually running our .NET code. After much deliberation we made the call to write a small application that is packaged in Dev-Local-Setup and can reverse proxy and perform the process management that IIS used to do for us based upon host header. That application is called KestelProxy.

Nobody wants to write another reverse proxy, so we initially started to use the AspNetCore.Proxy NuGet package to handle the reverse proxy shennanigans for us. We’ve since moved to using YARP as it has better integration with the Kestrel pipeline - it’s possible we’ll be using it in more scenarios in the coming months so having something we can use in a few places has less cognitive overhead! We’ve done very little customization of the proxy itself, our changes have been purely in dynamically registering applications using Dev-Local-Setup and managing the underlying dotnet process lifetime.

Individual teams contribute to Dev-Local-Setup to configure their applications and each has a piece of configuration like this:

| |

This configuration is used by Dev-Local-Setup to generate certificates for HTTPS, update hosts entries, grant access to databases and to configure the websites in either IIS or KestrelProxy. When a user of Dev-Local-Setup runs the menu option to configure the websites associated with their team, we read this configuration and use it to update the KestrelProxy’s appsettings.json file. This registers the host headers (and any aliases) along with the location of the project, any command-line arguments and environment variables with KestrelProxy.

When KestrelProxy reads its configuration it uses the IBackendsRepo, IRoutesRepo and IReverseProxyConfigManager services exposed by YARP to notify it that there are new routes to listen to.

| |

KestrelProxy is configured to launch with user privileges using launchd and it sets environment variables to ensure it listens on ports 80 (HTTP) and 443 (HTTPS) as well as being configured to use the certificates Dev-Local-Setup generated when configuring the projects. When a user browses to https://project.local/, or any of the aliases associated with a project, TLS negotiation works as expected and the request hits the KestrelProxy YARP pipeline. As part of the pipeline we ensure that the backend process representing the project has been started. If it hasn’t we execute dotnet run --no-build across the project directory - if the application hasn’t been built then that command exits almost immediately and we log an error. If it has been built then we wait until the process has started and continue the YARP pipeline to dispatch the request to the underlying process.

When we start the process representing our project we set the ASPNETCORE_URLS environment variable to a dynamically generated HTTP endpoint - YARP forwards the request to that endpoint as part of the proxying pipeline. This is similar to how IIS would do things if it was running an ASP.NET Core application out-of-process - it starts a process and forwards requests from IIS to that process.

All of this means that there is a long-lived web server that is started when the user initially logs in. There’s a very simple UI showing the list of running sites, logs and any errors (using Exceptional) - that looks quite a lot like this:

KestrelProxy UI

What’s Next?

We have some developers and designers using this day-to-day, so we’re hoping it gets battle-tested reasonably quickly. I’d like to get the KestrelProxy bits upto GitHub for other people to play with soon but need to remove the pieces that are very specific to us first!

Longer term we’re going to look at Project Tye as a way to orchestrate things across multiple projects - it has similar aims to Dev-Local-Setup (orchestrating containers, projects, etc) and it has a much nicer dashboard - things like logs from the child processes it spins up. I suspect Dev-Local-Setup could just be a way to generate the YAML that Tye needs to execute but we haven’t had time to try it out yet!